St Nicholas Church, Swafield

Officially a Chapel of Ease, St Nicholas sits proudly on a hill with beautiful uninterrupted views over the surrounding countryside, relatively far from the village settlements – the little village of Swafield is to the south in the valley below.

The church that we now see, with its thatched roof, was built in the 14th century, the nave and chancel were rebuilt and enlarged later in the 15th century. The roofline of an earlier building can be seen above the arch that leads into the tower.

The stunning 15th century nave roof remains, with arched braces running right up to the ridge across the 8m (26 feet) span – without ties! Nikolaus Pevsner describes the roof design as daring, so much breadth unsupported by ties. This wooden roof provides excellent acoustics for concerts and other events. The ridge is decorated with nine bosses along the ridge. The bosses still have traces of original colour, including five heads with faces standing proud of the roof, and four, perhaps Tudor(?) Roses. Evidently these bosses in former times were surrounded by elaborately carved tracery, but now not much more than the central figure survives.

Also surviving are some of the medieval paintings on the dado depicting 8 saints, below the chancel arch. The rood screen has lost its superstructure, but the base is solid and well carved, with later brattishing added along the top rail. The panels are rather dark but have survived the Reformation and subsequent purges with very little damage, just the lightest of scratchings across the faces. The paintings look to be the work of two different painters. The more competent artist can be seen on the north side; the saints on the south side are handled by a less able painter. Although the figures are painted by different artists, the use of the same stencil tools in the backgrounds of panels from each side indicates that the two painters were working together at the same time.

In other instances, on rood screens, the work of separate painting workshops can be seen on the same screen, so it is interesting to make the distinction.

|

St Andrew and St Peter |

St Jude and St Simon |

|

St James the Great and St John |

St Thomas and St James the Lesser |

But let’s look outside the church: the nave of St Nicholas has a thatched roof, and the chancel is now covered with slates, although its high east gable wall indicates that it once also had a thatched roof.

The slender tower was built of cut flints in the 14th century, with short western buttresses supporting just the ground floor stage. There is a three light 15th century west window and belfry openings on all four faces with flatter arches and two lights. At the first stage there are some former “sound holes”, for ventilation, now partially filled in and blocked with brick. At the top are four gargoyles at the corners and above is a battlemented parapet, decorated with some flushwork flint set in the stone.

The large 15C Nave windows, three each side, have decorative brick and stone relieving arches above them and a variety of grotesque headstops to the hoodmoulds. The windows are so big – they make almost a wall of glass in the nave.

At the north-east corner of the nave the window has been shortened to allow for the insertion of a stairway to the rood loft. The buttresses have neatly cut flints inserted in their faces and two of the ones on the south side have Mass Dials, an early form of sundial indicating when the services would take place. These were in use from Norman times until about 1400, when clocks as we know them became more easily available.

The south doorway appears to be 14th century, so perhaps it was reused, for this is a fairly early rebuilding in the Perpendicular style. The south porch entrance has a former grave slab as its threshold, recognisable because of its tapered shape. In the right-hand corner of the porch, there is a large bowl for water, Benetura, or HolyWater Stoup, which would have been blessed by the priest and where the congregation could dip their fingers and cross themselves as a sign of atonement before entering the church. The doorway has much graffiti cut into its stone, many of them crosses, and a small Mass Dial on the west jamb just below the end of the hood moulding.

The main door itself is ancient, of medieval woodwork, with 15C ironwork, consisting of a rectangular escutcheon plate, a ring plate and an oval ring. The ring plate has punched designs of lancets and circles. The ancient door lock, made with oak, still works.

If you go back inside the church, you’ll first see the Victorian font, which is placed in front of the tower arch.

On the north wall is mounted a Crucifix with an amazing history. The body was found washed out of a hiding place in the cliff, thickly covered with clay on Walcott beach in 1937, and its arms were subsequently picked up, one a mile away along the beach. Or it had maybe come from a church overwhelmed by the sea? These pieces were repaired, mounted on a cross and presented to the church in 1939.

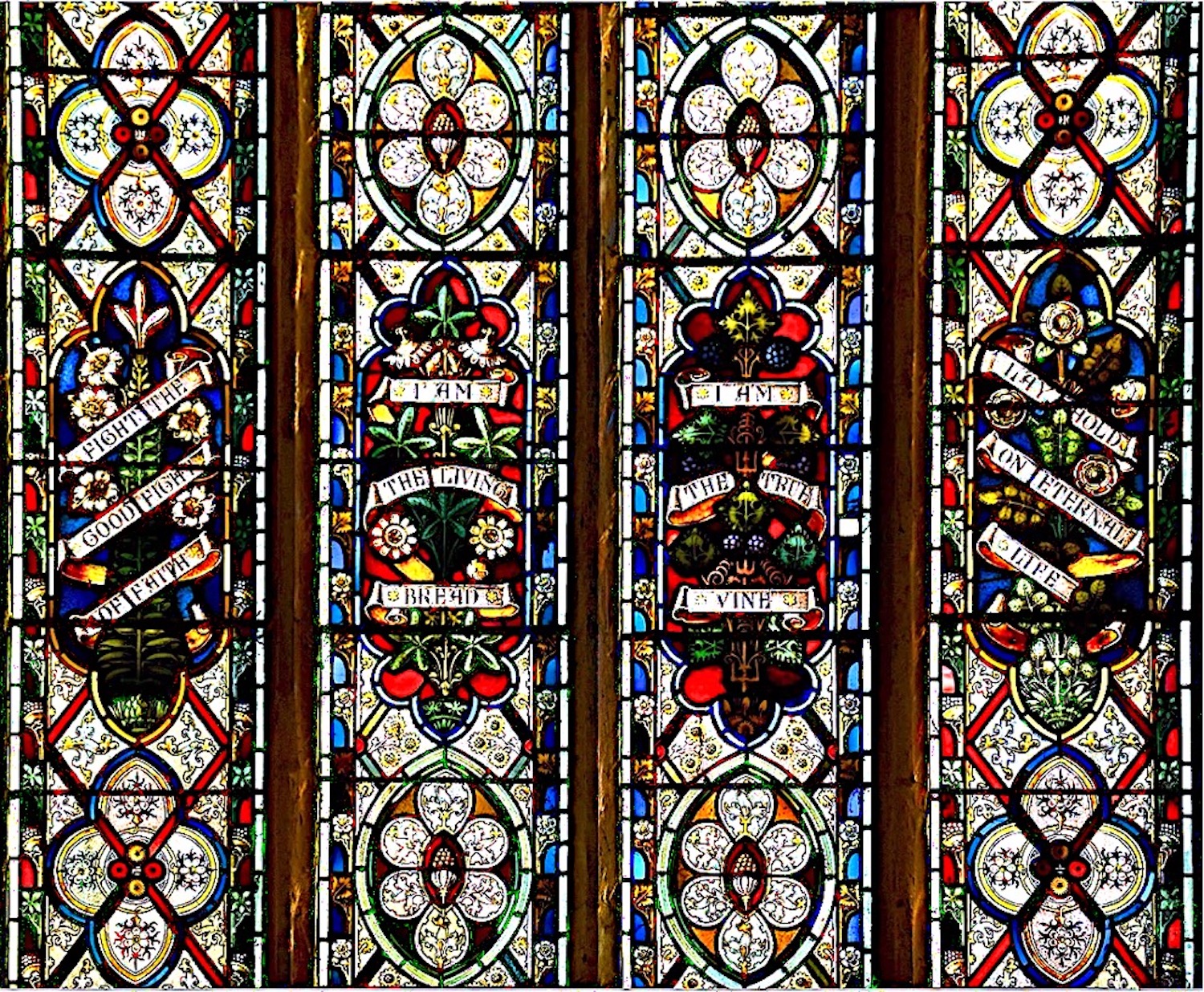

The east window contains Victorian patterned glass, c1880, with texts entwined in different plants, “Fight the good fight” (a lily), “I am the living bread” (a passion flower), “I am the true vine” (a vine), and “Lay hold on eternal life” (a rose).

The east window with Victorian patterned glass, c1880

The other stained glass is in the second window of the chancel on the south side, which shows St Cecilia with a portable organ, the Good Shepherd carrying a lamb, and St Nicholas with his symbol of three gold balls, (later used by pawnbrokers!). This glass, in memory of Henry Dolphin (1856 – 1881), and his brother Edgar Dolphin (1857 – 1889), was erected by their mother Charlotte Dolphin (1825 – 1917) in 1904. She lived with her family at Swafield Hall for 60 years. Two of Charlotte‘s sons, Henry and Edgar, joined the army. In January 1881 Henry was killed at the Battle of Laing’s Nek during the First Boer War in South Africa. He was 24 years old.

Charlotte’s youngest son Edgar Dolphin served as a captain of the 2nd Battalion, King’s Own Royal Regiment, in South Africa, India and Pakistan. In September 1889 Edgar, who was on leave of absence and was staying at Swafield Hall, accidentally drowned in Norfolk, on Wroxham Broad, at the age of 32.

The glass was made by Jones & Willis, one of the biggest firms in the latter part of C19 who manufactured church furnishing and stained glass. It’s written in the bottom of the window: “For the glory of God and in loving memory of Henry Dolphin who was killed at Laing’s Nek in Jan 28 1891 & Edgar Dolphin accidentally drowned Sept 21 1889 This window is erected by their Mother”.

The Dolphins seem to have been people of taste: there is a memorial window in St. Mary’s church in Antingham, erected by the Dolphins in 1868. It was commissioned from the rising firm of William Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & co. The cartoon for St Mary Magdalene is by William Morris himself. John Dolphin (Charlotte Dolphin’s brother in law) was the vicar of Antingham and Thorpe Market for 59 years and lived in Antingham Rectory.

The church pews were installed at St. Nicholas in 1861 with a £25 grant from the Incorporated Society for Buildings and Churches. The 22 side wooden panels of the pews, visible from the aisle, are covered with intricate carvings in gothic style, and not a single pattern is repeated.

St. Nicholas Church inside, 2025

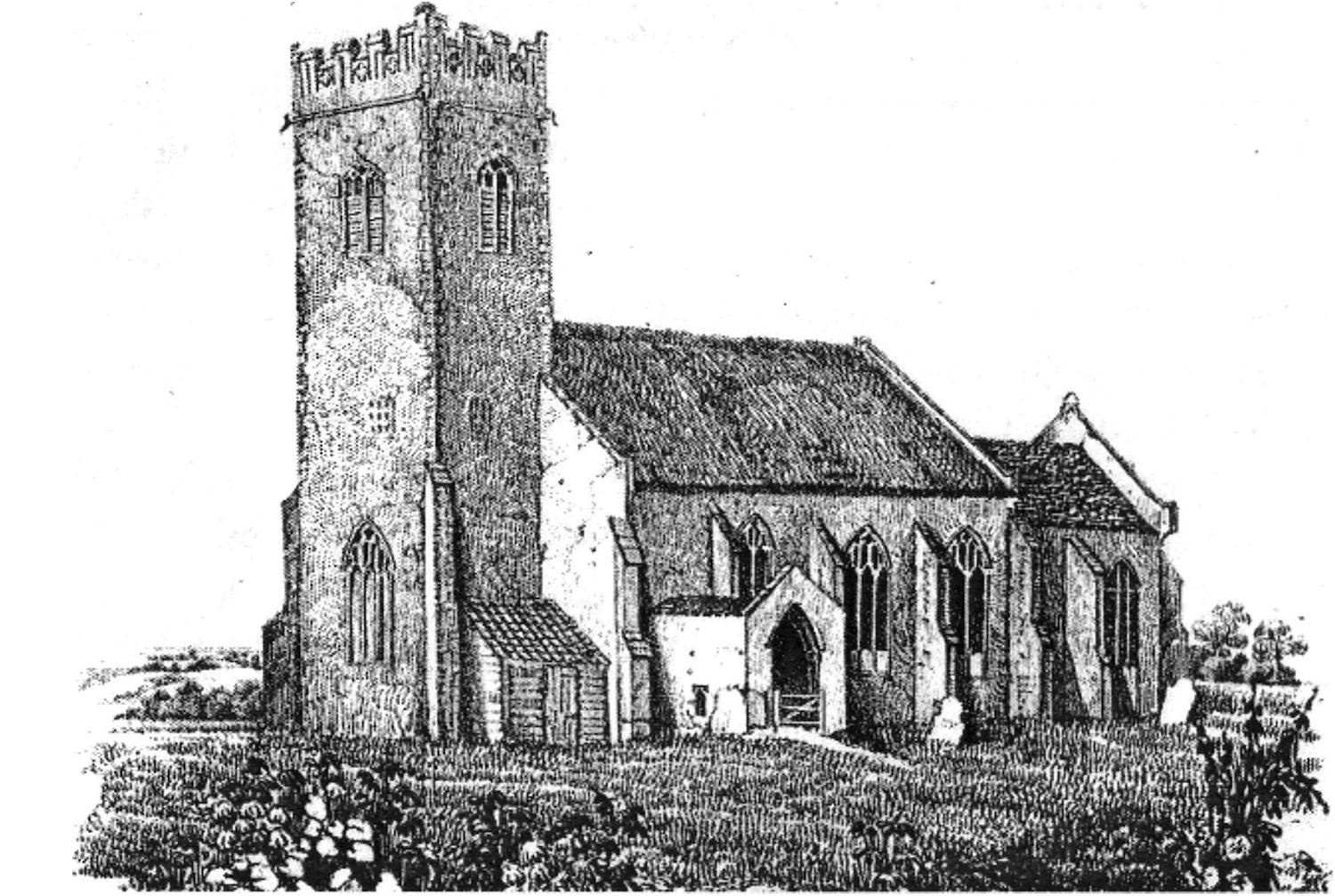

St. Nicholas Church drawn by Robert Ladbrooke in about 1820